- Home

-

Sample Tours

-

Sample Custom-Made Tours

>

- Sample Custom-Made Tours Highlights

- Spring: 7 Day Spring Variety 10pax Sample Tour

- Spring: 5 Day Southern Spring Blossoms Sample Tour

- Spring: 8 Day Hiking & Wildlife Luxury Sample Tour

- Summer: 7 Day Summer Variety Sample Tour

- Summer: 7 Day Hiking & Sightseeing Sample Tour

- Summer: 6 Day Hokkaido Heartland Sample Tour

- Fall: 8 Day Fall Foliage Family Fun Sample Tour

- Fall: 8 Day Central & Eastern Hokkaido Fall Luxury Sample Tour

- Fall: 6 Day Fall Variety & Scenic Roads Sample Tour

- Winter: 7 Day Winter Wonderland Sample Tour

- Winter: 4 Day Winter Family Fun Sample Tour

- Winter: 7 Day Winter Active Luxury Sample Tour

-

Sample 2-Day Tours

>

- Sample 2-Day Tours Highlights

- 2-Day Tour Lake Toya, Lake Onuma & Noboribetsu

- 2-Day Tour Niseko, Shakotan Peninsula & Otaru

- 2-Day Tour Tokachi, Furano & Biei

- 2-Day Tour Snowshoeing, Ice Fishing & Furano

- 2-Day Tour Asahidake & Sounkyo Snowshoeing

- 2-Day Tour Asahikawa, Dogsledding & Daisetsuzan

- 2-Day Tour Asahidake Onsen & Sounkyo Gorge

- 2-Day Tour Takinoue Pink Moss, Tulip & Biei

- 2-Day Tour Mountain Hut Overnight Hiking

-

Sample Day Trips

>

- Sample Day Trips Highlights

- Noboribetsu & Lake Toya Day Trip

- Furano & Biei Flower Fields Day Trip

- Shakotan Peninsula & Otaru Day Trip

- Mt. Tarumae & Mt. Moiwa Day Trip

- Jozankei & Niseko Fall Foliage Day Trip

- Asahikawa & Mt. Asahidake Day Trip

- Mt. Asariyama Snowshoeing & Onsen Day Trip

- Ice Fishing & Dogsledding Day Trip

- Furano Snowmobiling & Ice Fishing Day Trip

-

Sample Custom-Made Tours

>

-

HNT Insight

- Awards, Reviews & Accolades

- FAQ

- HNT Blog

-

Hokkaido Activities by Season

>

-

Spring Season

>

- Spring Sightseeing

- Spring Gourmet

- Spring Festivals & Sakura

- Hot Spring

- Spring Wildlife & Zoos

- Farm Visits & Horseback Riding

- Boat Excursions

- Hiking & Trekking

- Hot Air Ballooning

- Adventure Activities: Spring

- Resort & Backcountry Spring Skiing & Snowboarding

- Daisetsuzan Nat'l Park: Spring

- Crafts, Culture & Cooking

- Summer Season >

- Fall Season >

- Winter Season >

-

Spring Season

>

- Contact Forms

|

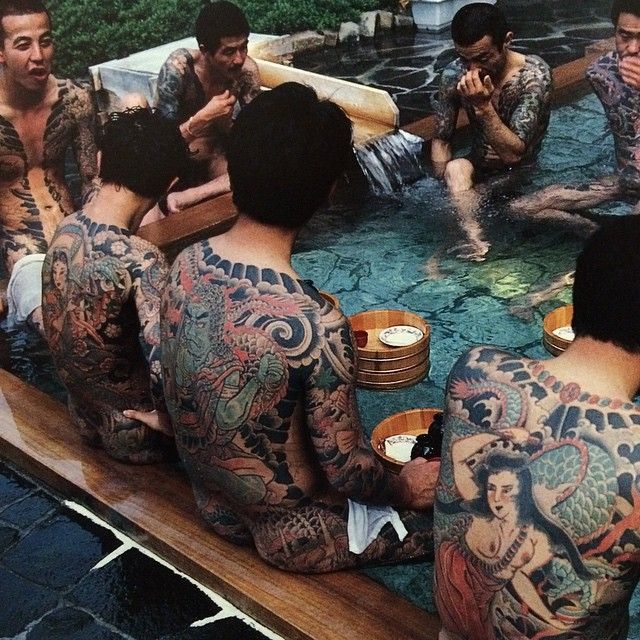

Beyond the poetry (see The Heart of an Onsen: Part 1), there are a few essential rules for how to behave properly in an onsen, better known as yarikata – the way something is done. So, throw your earthly possessions in a basket in the dressing room, lock up your valuables in a lockbox (jewelry & watches are not recommended in the hot springs), summon your courage along with a small onsen towel, and let’s bathe! The Naked Truth Many foreigners who visit Japan feel uneasy about public nudity at onsens. Back home, bathing is done in private and away from the leering eyes of others. For most people, that discomfort lasts for just a few minutes once they realize that everyone else is naked too! Japan is an egalitarian society, and that is epitomized at an onsen. While bathing, it no longer matters what position one holds at a company, what car one drives or in which neighborhood one lives. Everyone is truly, nakedly, equal. That said, don’t be surprised if you get a few stares at your nether regions. After all, in Japan it’s the foreigners who are exotic! If that doesn’t work, just remember that Japan actually has a festival that honors the “slippery serpent” - not quite the image most people have of Japan, right? The Onsen Towel The only object that is permitted past the dressing room is the small, conspicuous, barely-there white towel. The towel is used both as a wash cloth and to (somewhat) cover your nakedness while walking between baths. While in the hot springs, it is considered impure to dip towels in the water, which is why you should either place the towel at the edge of the bath, or fold in a square and rest it on top of your head. Wash Before You Bathe It is essential to completely wash your body before going into a hot spring pool since hot springs are common spaces in Japan. More so than in nearly any other country, Japanese people show respect to others in common spaces such as subways, parks, shops and of course, at the onsen. While we’re at it: Don’t talk loudly while bathing, it’s also considered rude. Washing Stations Next to the shower you'll see a little chair and a bucket. Sit in the chair and soak your onsen towel in the bucket. Almost always there are body soaps & shampoos provided, and most Japanese people prefer to lather up their onsen towels to scrub every centimeter of their bodies. I have seen people spend over a half hour just scrubbing themselves, to the point where their skin turns red, before they ever enter the baths. Going to a hot springs is probably the most accessible form of a Japanese purification ritual that foreigners can witness. Post-onsen You can lounge around the bathing area and enter the baths as many times as you like. The real old-timers stay in for at least an hour. Once you’ve had enough, you can either rinse off at the washing stations or head straight back to the dressing room. One last rule: Don’t enter the dressing room dripping wet. Use the onsen towel to dry yourself a little, then enter the dressing room and grab your full-length towel from your basket, or simply air-dry. At bigger onsens you can find various beauty products invitingly set in the dressing room: Hilauronic acid, collagen, placenta, royal jelly and other well-branded cosmetic giveaways always make me happy to spend extra time taking good care of myself. If you want to finish off your bath in a truly Japanese way, head for the vending machines and grab yourself a small bottle of milk. There is the belief that milk rejuvenates the body after bathing. In some onsens you can still find signs at the entrance informing visitors that tattoos are not allowed. It is an anachronistic custom of a bygone era when tattoos were attributed to yakuzas (mafia), the dominant criminal group of post-war Japan. If you are the bearer of tattoos, small ones can be covered up with your onsen towel, and larger ones, well…either hope the staff doesn’t say anything, or avoid the cleaning ladies at all cost – your hot springs may depend on it. If you are asked to leave, there is really no point in arguing. Obviously, as a foreigner, you could never be a yakuza; but after all, this is still Japan, where yarikata is bigger than any of us. At least you are now aware of the essential yarikata of taking an onsen. But there is one rule we neglected to tell you so far: leaving Japan without visiting at least one onsen is, well, criminal!

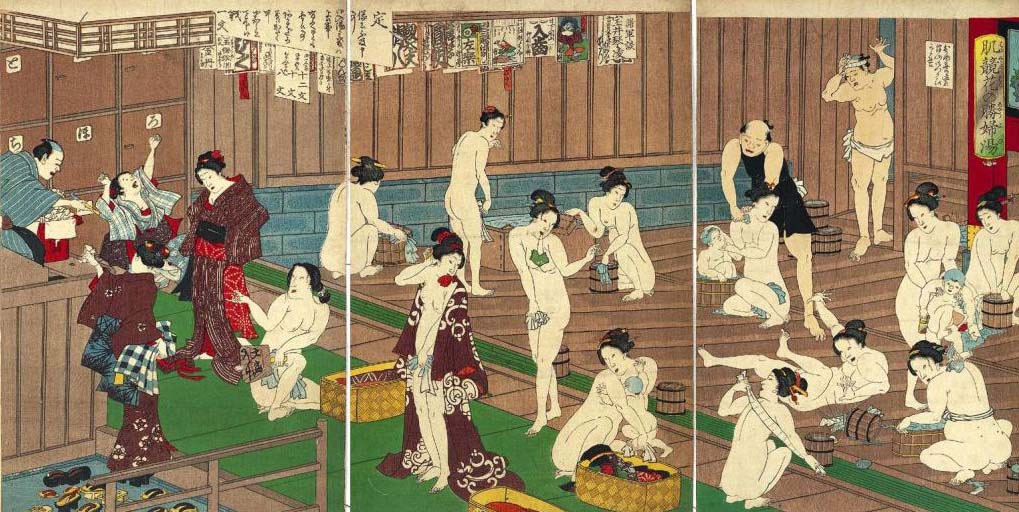

Enjoy Nature, Be Happy! Anastasia at HNT Every traveler who sets their mind on writing about Japan inevitably and wholeheartedly comes to talk about onsens - Japanese hot springs. There are many reasons why. First of all, Japan is an archipelago, located in the ring of fire, where two massive tectonic plates collide to create incessant volcanic activity. The fertile volcanic soil and multi-hued water are rich in minerals of all kinds: Iron, magnesium, calcium and sulfur to name a few. According to Wikipedia, “The legal definition of an onsen includes that its water must contain at least one of 19 designated chemical elements and be 25 °C or warmer before being reheated.” There are more than 3000 established onsens in Japan and in every guide book an onsen visit is recommended as a must-do. Towns and prefectures compete with each other for the title of "the best". It might disappoint you to hear it, but there is no such thing as the “best onsen in Japan”. There is too large a variety for such a label to apply. There is the largest, the oldest, the most modern or traditional; child-free, mixed, geisha approved, yakuza welcomed; at the lake shore, by the sea, at the foot of a volcano, wild onsen, onsen with hot rocks, mud baths, mineral-rich, medicinal, and even fruit-scented, coffee-suffused and tea-drawn pools. One could spend a lifetime soaking in them all. Onsens are not only touted for their natural beauty and health-restoring benefits, but they are perhaps the quintessential Japanese cultural experience. Indeed, for every Japanese person, going to an onsen is an indispensable ritual. The very creation myths of the Yamato race reflect the disgust of polluting the body and spirit, and the bliss of undertaking rites of purification. This obsession with cleanliness and purity is displayed in full-force at an onsen – and even eclipses the otherwise prude Japanese culture through ritualized group nudity - and we’ll soon reveal how that process unfolds. For someone like me who grew up in the northern climate of the far east of Russia, public baths, called banya, are a common fAeature of everyday life. Alternatively, many of my non-Russian western friends feel ashamed at showing their bodies in public. In the US for example, there isn't such a thing as public bathing. Bathing is something very private that is done at home, locked away from other family members. In Finland, at the other extreme, public bathing is usually mixed-sex, so bathing with the other gender is completely accepted. Historically in Japan as well, men and women bathed together, but gender separation has been enforced since the opening of Japan to the West during the Meiji Restoration 150 years ago. Nowadays, mixed-bathing, or konyoku, is only found in out-of-the-way rural communities. Let's take a closer look at the Japanese ritual of an onsen. Every onsen has common features, such as changing rooms, showers and baths: it is of course the latter that gives an onsen its reputation. An outdoor bath, called rotenburo, is the heart and soul of an onsen. Here, in a beautiful natural setting, you can let go of all the stress of day to day life to reunite yourself with nature, nourish your body, and purify your mind with beauty and peace. Not every onsen has a rotenburo, and not every rotenburo is beautiful; but those that are provide a true contemplative and meditative experience. Japanese people can sit in a rotenburo for hours when the feeling is just right. The setting of a rotenburo is the most crucial element in an onsen’s success: overlooking a rocky cliff with a flowing river below; a gushing geyser with mineral-colored soil; a placid lake at sunset, shading the water purple and pink; a valley with a mountainous backdrop in full autumn colors; or a yukimiburo, or snow viewing bath, at the edge of a forest. Such moments, when you're sitting in a rotenburo amid the falling snow, watching it land on your shoulders and disappearing in the steaming hot springs water – those moments and impressions help define Japan. Such experiences are pure ecstasy for the poetry-prone Japanese heart; but you certainly don't have to be Japanese to feel such bliss. Read about the etiquette of visiting an onsen - from well-known to esoteric rules and rituals - so you’ll know exactly what to do, and more importantly, what not to do, on your next visit to an onsen, in part 2 of this blog entry.

|

Welcome!Our blog covers any and all topics of travel in Hokkaido - from the best gourmet oysters to off-the-beaten-track adventures - and everything in between. Archives

September 2021

|

|

- Home

-

Sample Tours

-

Sample Custom-Made Tours

>

- Sample Custom-Made Tours Highlights

- Spring: 7 Day Spring Variety 10pax Sample Tour

- Spring: 5 Day Southern Spring Blossoms Sample Tour

- Spring: 8 Day Hiking & Wildlife Luxury Sample Tour

- Summer: 7 Day Summer Variety Sample Tour

- Summer: 7 Day Hiking & Sightseeing Sample Tour

- Summer: 6 Day Hokkaido Heartland Sample Tour

- Fall: 8 Day Fall Foliage Family Fun Sample Tour

- Fall: 8 Day Central & Eastern Hokkaido Fall Luxury Sample Tour

- Fall: 6 Day Fall Variety & Scenic Roads Sample Tour

- Winter: 7 Day Winter Wonderland Sample Tour

- Winter: 4 Day Winter Family Fun Sample Tour

- Winter: 7 Day Winter Active Luxury Sample Tour

-

Sample 2-Day Tours

>

- Sample 2-Day Tours Highlights

- 2-Day Tour Lake Toya, Lake Onuma & Noboribetsu

- 2-Day Tour Niseko, Shakotan Peninsula & Otaru

- 2-Day Tour Tokachi, Furano & Biei

- 2-Day Tour Snowshoeing, Ice Fishing & Furano

- 2-Day Tour Asahidake & Sounkyo Snowshoeing

- 2-Day Tour Asahikawa, Dogsledding & Daisetsuzan

- 2-Day Tour Asahidake Onsen & Sounkyo Gorge

- 2-Day Tour Takinoue Pink Moss, Tulip & Biei

- 2-Day Tour Mountain Hut Overnight Hiking

-

Sample Day Trips

>

- Sample Day Trips Highlights

- Noboribetsu & Lake Toya Day Trip

- Furano & Biei Flower Fields Day Trip

- Shakotan Peninsula & Otaru Day Trip

- Mt. Tarumae & Mt. Moiwa Day Trip

- Jozankei & Niseko Fall Foliage Day Trip

- Asahikawa & Mt. Asahidake Day Trip

- Mt. Asariyama Snowshoeing & Onsen Day Trip

- Ice Fishing & Dogsledding Day Trip

- Furano Snowmobiling & Ice Fishing Day Trip

-

Sample Custom-Made Tours

>

-

HNT Insight

- Awards, Reviews & Accolades

- FAQ

- HNT Blog

-

Hokkaido Activities by Season

>

-

Spring Season

>

- Spring Sightseeing

- Spring Gourmet

- Spring Festivals & Sakura

- Hot Spring

- Spring Wildlife & Zoos

- Farm Visits & Horseback Riding

- Boat Excursions

- Hiking & Trekking

- Hot Air Ballooning

- Adventure Activities: Spring

- Resort & Backcountry Spring Skiing & Snowboarding

- Daisetsuzan Nat'l Park: Spring

- Crafts, Culture & Cooking

- Summer Season >

- Fall Season >

- Winter Season >

-

Spring Season

>

- Contact Forms